Maybelle was a bad doll, but she couldn’t help it. The wood that she’d been carved from was terribly damaged. Only one person knew that, and he wasn’t telling. He couldn’t. He was dead. The act of creating her had been the last thing he did. He hadn’t planned it that way.

Drogon was the village doctor – medical and otherwise. If you were out of sorts, you went to Drogon. Before that you’d have gone to Drogon’s father, and now you’d have to go to Drogon’s son, even though he was only seven. These kinds of doctors didn’t get trained in schools, or even by their parents. There was no apprenticeship. The moment the father breathed his last, his spirit and everything he’d learned traveled into the son. It had gone on so long that everybody in the village accepted it as normal, just like how flowers came out in the spring and leaves went away in the fall. The village was many miles from any other so the residents had no way of knowing this was unusual. It was only in the past decade that they’d even learned they weren’t the only people in this country, or even on the planet.

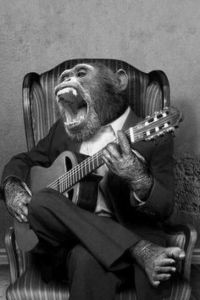

They’d never ventured any further than a few feet from “the edge of the world” as they called it. Why would they? Everything they needed was here. Exploration comes from want and need. If you have everything you want or need, you don’t tend to go exploring. Art was created for the same reason – out of a sense of lack and loss. Folks who felt content weren’t artists. Artists were forever plagued to create even more art, because what they made never felt quite right to them. The fact that they had a sense of something missing in the world caused them to make art – but then still feel incomplete.

Drogon was an artist as well as a doctor – never satisfied with his work. He was certain he could do better with his healing. This was unlikely, since he’d inherited 16 generations worth of healing knowledge when his father died. Everything his father had learned had passed on to him, as it had happened to himself when Drogon’s grandfather had died. It was an amazing process. One day you were yourself, the next you had all these voices in your head giving you unsolicited advice on what to do. It was a little like a family reunion but only one person heard the jokes, and thankfully nobody brought the green bean casserole.

Not many years after their first visit from the outside (as everything other than the village was called), Drogon had a visitor from very far away. He was told that everyone there spoke a different language than him and thought differently, acted differently, dressed differently. He was told that they weren’t as clever as the villagers, because they couldn’t make up stories to entertain themselves in the evenings. He was shocked to learn that hundreds of people would even pay to sit and listen to a person entertain them, to tell them stories, even hearing stories through the air on something called television, rather than in person. Drogon thought that there must be a huge drought on stories there to have to go to that extreme.

This visitor wanted Drogon to make her a very special doll – one that could tell stories to her people. She’d had a successful career as a ventriloquist, but this would be different. This would be special. This would be so amazing that she could retire early, at the top of her game. She wouldn’t have to suffer the indignity of having to do ads for life insurance or hearing aids in her later years, as so many of her fellow performers did. She wouldn’t have to hawk (or hock) anything. She’d be set, if only he would make this new dummy with some of his magic. She told him nothing of her own needs – only that he would be helping her people with their story-sickness.

Drogon had assured her that he had no such skill, no ability to make wood talk, but she was persistent, and he soon felt sorry for these people so far away who had to pay someone to do something they could do for themselves. He promised nothing, but said he would try. That night, he did something he’d never done before – he called a family conference.

That night, he called together all 16 generations of healers from his family. Never before had Drogon even attempted to rouse them. Normally they were just there in his head when he needed them. But this was different. This was a sickness as sure as malaria, as certain as cholera. To be without stories was a sickness of the soul, a certain death. Sure, you could live without stories, but it would only be half-life, a sorry existence. He told his ancestors, all those healers before him, that they would be giving the greatest gift of healing they could ever give if they would do this one thing for him.

It took them eight days to agree to try, and another ten to figure out how. Three more days and the performer from the faraway country was leaving. Drogon had to act soon on their suggestion. He wasn’t sure if it would work but he had to try. Early the next morning, before the sun had risen but after the birds have begun to sing, he went to the center of the village to the story tree. This was the tree where they all met every evening for stories and at least once a week for council. It was the center of the village. As far as anyone knew, it was the reason the village was there.

The tree at the center of the village was older than memory and bigger than dreams. A dozen grown men could stand around it with arms outstretched and embrace it in a circle. Its branches stretched out 40 feet all around and were thick enough to provide shade on the hottest of days and protection on the wettest ones too. Drogon looked at it, this member of the village he’d known the longest, and told it his tale. He asked it for its permission to do what must be done to cure the people he’d never seen, would never see. He told the tree that they would sing songs about it for years in the future, to honor its sacrifice of itself. There was no answer back. He hadn’t expected one, but he had tried all the same. He’d tried because to not try would have meant the guilt of what he was about to do would be on him and his descendants forever.

He assumed all must be well with the tree’s silence. “In silence it went to the slaughter, a willing sacrifice, the cure for their disease.” The lines of a half-forgotten prophecy came to him then and he felt better. Surely it was about this time, and this event? He felt the odd tingle of power that always happened when a prophecy came true, when to be became now.

With spirit ghosts from all of his ancestors helping, he had the tree chopped down in less than an hour, and quietly enough that none of the villagers awoke.

He had selected one log to use for the doll. It was from the heart of the tree, and was a warm sepia, the color of dry autumn leaves, the color of coffee with a hint of cream, the color of the people it had loved for so long. He had planned to carve it himself afterwards to complete the ritual, but first he had to call the spirit of the tree into it.

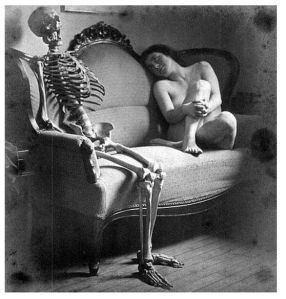

Right now it was like any other spirit after a trauma – floating around in the air, hovering close to its body. Car accident victims were the same. The spirit gets pushed out before it has a chance to realize that the body is no longer a safe vehicle for it. Meanwhile, it hasn’t prepared itself for the journey it must now embark upon to return to the All-spirit.

Many souls think they have years before them to prepare for that mapless and solitary trip. Some are surprised at a sudden death and they linger around the body longer than they ought. There was a danger to living humans in these places – the spirit might try to take over, to evict the living soul, or to try to double-up. This led to what the villagers called “possession”, and what Westerners called “mental illness”. Some spirits stayed in the area of the accident for weeks afterwards, the body buried elsewhere. This meant that it was possible to cross paths with a homeless spirit without even realizing it. Perhaps this was why some people in America had started putting up roadside memorials at the site of a fatal car crash – to subtly warn others of the risk of contamination. Perhaps they knew this truth deep down, on a subconscious level.

Drogon meant to call the spirit into the wood but it was harder than he’d imagined. None of his ancestors had ever been through anything this immense, so they couldn’t offer anything useful in the way of advice or warning. They were all winging it. They knew it was in their best interest, as a group, to be as careful as possible. This much energy in one place could possibly make all of them wink out of existence.

There was a reason that tree had been so big – it had held the hopes of the village for thousands of years. It had fed them with stories the same as a mother feeds her babies with milk from herself. It had sheltered them as a mother hen shelters her chicks. All of that spirit was too much to try to condense into one tiny log, but it tried. Perhaps the tree wanted to help out those nameless people who were so far away. Perhaps it trusted the village doctor, who had sat under its branches in the cool of the evening, just like his father and his father on back into the mists of time. He wouldn’t bring harm, no, not him. So the tree sacrificed itself, went easily, almost willingly. And yet it still was too much spirit to distill down into one log meant for one little doll. The energy poured in, but once the log was full (over-full, actually, in the same way you can cram more sugar into tea if you pour it in while it is hot), it spilled out, and up, and over Drogon, and in a flash of blue-violet light, embraced him, and erased him.

The sound that was created in that moment was like the sound of a waterfall swollen by spring rains, or that of a thousand bees swarming to find a new nest. It was sudden and sure and scary, like a lion before it charges upon a hyena foolish enough to prey upon his family. It was then that the rest of the villagers awoke to discover the remains of Drogon next to the felled tree. They ran to find Drogon’s son, knowing that he would now be able to explain what happened. The only reason they knew it was Drogon was from his clothes and the beaded jewelry he always wore. His body had been reduced to ash.

Drogon’s son, only seven years old but now the village doctor, took it upon himself to complete the doll. It had to be done. Otherwise, the death of the tree would have been in vain. He also had to atone for the actions of his father, as well as the ancestors who had agreed to this disastrous plan.

Out of a sense of guilt, the lady from the faraway land offered the villagers ten times the amount of money for the doll than she had originally agreed to. They wanted nothing – no money, no school, no hospital. Nothing could repay them for the loss of their tree. To accept payment would be to cheapen its sacrifice. They gave her the completed doll, hoping to never see it or her ever again.

The lady went on to become famous for her ventriloquist act, retiring earlier than she’d hoped. Her fans were amazed at how much better she had become. The skits were sharper, wittier, if a little edgy these days. They marveled at how adept she had become at throwing her voice without apparently having her mouth open.

She kept the doll with her all the time to keep her secret. She lived alone for the same reason. When she had first returned from her trip, she was living in an apartment, but soon made enough to move to a large home, far away from people. This was good, because otherwise they would have heard the wooden dolly arguing with her owner.

It all came to an end one humid summer night when the home went up in flames, reducing both the lady and the doll to ashes. Arson investigators scoured the ruined property shaking their heads. They agreed that the fire looked like it was set on purpose by the doll, but since this made no sense, they quietly agreed to officially state that the performer had dropped a cigarette while smoking in bed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.