Edward had always been an unusual child. His teachers expected him to become an unusual adult too. His parents? Well, that was another matter entirely.

They never said exactly how Edward came to them, or even how he came to be. Bea and Charles, Edward’s parents as far as the world was aware, left town for a year a while back. When they returned, they had Edward with them. He was just over a month old they said, but some who looked in his eyes knew, just knew deep down in their bones that this child was far older in all the ways that counted. “He’s an old soul” they said, not knowing how true those words were.

Of course, not everyone could see the whirling abyss of time in his eyes. It was like looking into a dark disused quarry filled with rain water. You couldn’t see the bottom, and to some that was so frightening that their minds simply refused to look, to even get near. Those hidden depths spoke of secrets, of danger, of loss.

For some, Edward himself was invisible simply because of the dangerous unanswered questions that lurked like unwelcome promises behind his eyes. Their minds couldn’t accept their challenge, so they simply refused to acknowledge Edward’s presence, his very being. What Edward was could not be to them, so for them he was not.

Bea and Charles could see him better than anyone else, and they were grateful. They’d prayed for such a child, a “gift” as they called him, privately, fervently. The home they were living in now was a gift too, provided upon the introduction of Edward to his grandfather. For years they had scraped by, living with friends, or in trailers, or even in the library during the day and their battered Range Rover at night. The arrival of Edward had turned their lives around for the better.

A grandchild was all Bea’s father wanted from her. He promised her the house, paid off, furnished, utilities, the lot, on the day she and Charles married provided that they gave him a grandchild in due time. He made sure to explain it wasn’t just any house on the table, not one of her choosing. It was to be the house by the lake on the family estate. Her sister Eloise already had the woods house, and brother Tom had been gifted the one by the cold gray boulders. Only the big house remained, and it was occupied solely by Edward’s grandfather, known simply as “The Grandfather”, made so by the births of all his children’s children, now gathered like chicks on the family land.

Edward would have no siblings. The cost was simply too high. No money had changed hands for his conception. Money was just paper after all, just the promises of dead trees. Those who had brought Edward into the world needed something more solid than that.

Bea and Charles had been desperate to have a child, and the cost was nothing in comparison to the debt they were in. Who counts the expense when you stand to gain everything? It was like floating a check right before payday – something they knew very well.

They still didn’t understand what was to be expected of them for this “gift”, even though they’d signed a contract. There were fertility tests the doctors did beforehand, to make sure the couple didn’t have to pay such a price, could conceive on their own, but it was to no avail. Bea suspected some of her cells were taken then, for some other cause, but she didn’t dare to think about it for too long. All that mattered was that she had her child now. What happened in the future would just have to wait until then to be worried about.

Edward was always cold. Outside, on a warm July afternoon, he always wore a jacket or coat. Charles got his tailor to make a blazer for him out of the thickest tweed he could find. The colors looked like the bracken and gorse that surrounded his Uncle Tom’s house. When he was inside, a fire was always going in whatever room he was in.

At first, he insisted in his own way that all the fireplaces would be working all over the house, but Bea and Charles soon realized his subtle influence over them and set some boundaries. Even as a baby he was able to make people do his will. Even without speaking he could turn them, bend them. His parents didn’t realize he was influencing their minds until the fires.

Edward had never seen a fire until he was a year old. Before that his parents bundled him up in sweaters and blankets to stop his shivering. They simply hadn’t gotten around to having the chimneys inspected in that old stone house, so they had no fire out of fear. The moment they were able to light one, Edward wouldn’t leave the room, delighted with his newfound unencumbered warmth. When Charles tried to remove him from the room at supper time, Edward howled and kicked Charles in the shins. Not wanting to get into a fight with his son, Charles desisted and instead brought up a tray. They all ate supper together that evening, sitting by the fire, seated on the antique Persian carpet, the arabesques and swirling flowers in the design dancing all the more by the flickering firelight. Bea thought it was charming, like a picnic.

The charm wore off after week when Edward still refused to leave the fireside. They drew him out only after they lit fires in all the other rooms. Only then would he venture from his toasty lair. After a few months though, Bea and Charles had grown tired of the constant work involved in finding seasoned wood in town and then chopping it to size. Grandfather would not allow them to cut down trees on his land, not for Edward, not for anyone. They explained to Edward that it had to be one fire from now on, in only one room, and he could wear sweaters like before if he needed to wander anywhere else in the house. He sulked for a month in that room, unwilling to get cold.

They’d not wanted all that heat, especially going from spring into summer, but Edward did, so he simply placed his thoughts over theirs, like how a voodoun priest exerts his will over a zombie. He didn’t realize they would break free of his influence, his control of their actions, and certainly not so soon. For the longest time they thought they too were cold and needed the heat just like he did. It was only when Charles passed out from heat exhaustion one Tuesday that they started to question their actions, realizing that they didn’t want the house to be at 92°.

From that point on they questioned everything they thought. They wondered what passed through their minds was their thought, or Edward’s. He tested them to see how far his influence went. He tried simple things, like food cravings. For one week they craved bananas and they ate them like they were going out of style. A different week it was strawberries. That was a mistake, Edward soon learned, because Bea was allergic, had been since she was a child. She knew she wasn’t craving them, that it had to be Edward’s doing.

He had to figure out another way to get his needs met. He finally, reluctantly, decided to let them teach him their language. That dry chittering sound grated on his ears. It was so unlike the warm liquid sounds he knew as his native tongue. His mouth ached with the effort of shaping the sounds for them, but it was the only way.

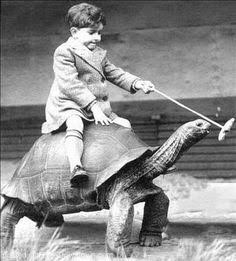

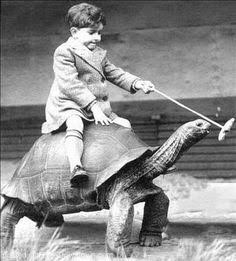

When he was three they took him to get a pet. Bea decided he needed a companion. A dog was ruled out straight off the bat – the warmth Edward needed would make it lethargic at best, dead at worst. A tortoise, a Galapagos tortoise to be precise, was decided after careful and discreet inquiries with the local librarian. She explained how they are cold-blooded so they need warmth, and how they live for many years. This added quality helped to tip the scales.

The elders who had helped them hinted that their true age was far beyond their appearance. Their kind were old at birth, having already lived half a human lifetime in a middle dimension, one where they were spirit only. This gave them certain advantages. They could learn quite a bit without the bother of a body. No colds to catch, no growing pains, no accidents, no trips to the doctor or the emergency room or the morgue. They even got to skip all that awkwardness of puberty while they were learning. Only when they had gathered about 50 of our years worth of knowledge did they bother to incarnate, and only then into a bespoke body, tailored to their temperament and needs. Certainly then there were the usual risks of being embodied, but by then they knew how to navigate safely through those obstacles.

Bea and Charles only suspected at the truth behind their benefactors, the ones who had given them Edward. The Grandfather would never know. For him, Edward was of his flesh and blood and that was all he needed (or wanted) to know. No matter that Edward was decades smarter than any of his other grandchildren. If he’d known the truth about this cuckoo child, he’d throw him and his parents out and never speak their names again.

Edward was their child in deed if not in act. He never grew in Bea’s womb, but he did share her DNA, as well as Charles’s. The elders didn’t mention there was a bit more to the mix than just the two, however.

It was kind of like fruit juice. How much actual juice was necessary for it to still be juice? Perhaps there are vitamins and minerals added to improve the quality. Perhaps other things to make it last longer. Sure, at the end it still looked and tasted like juice, but really only 50% of it was straight from the vine. It was kind of like that with Edward and his parents, but in their case it was more like 5% than 50%. They’d never be the wiser. Edward was theirs, and that was all they cared about. And of course, they were parents in the way that mattered most – they loved him, took care of him, and make sure he was happy and wanted for nothing.

Well, they didn’t give him everything. That would spoil him. And after all, they still had to make sure he wasn’t using the old mind push on them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.