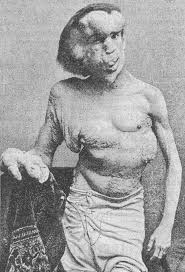

He was a monster, but only on the outside. The real monsters were those who stared at him outright, or talked about him in hushed tones as he passed. He couldn’t help how he looked, but they could help how they acted – but never did. His various doctors over the years exercised cool detachment as one would expect from professionals, but then again they were under his employ. People can usually at least pretend to be nice if there is money involved.

The doctors were certain of the disease, but not so much on the cure or even the cause. They knew only the symptom but not the source. They took his money and made him feel special, but never once let on that there was no cure, only care. They could refer him to clothiers who would happily create bespoke clothing to fit his unusual frame. They knew of carpenters who could construct a bed that would allow him to sleep semi-upright to relieve the pressure on his overworked neck.

Only one person knew the true cause of his deformity, and he wanted no money for the tale. Money wouldn’t cure him anyway, nothing would. John had crossed the wrong spirit one Tuesday night in October when he was 15, and he didn’t even know it.

Movies were a dime on Tuesdays at the downtown three-screen theater and a quarter all other days. Even though Tuesday was a school night, John was allowed out to see the latest film once a week as long as he kept his grades above a B. Even a B- wasn’t good enough and would make him lose this privilege for a whole quarter until the report cards came out again. So every other day of the week he went alone to the library to study so he could go to the movie theater on Tuesdays. Sometimes he went with friends, but he was just as likely to go by himself, savoring the peace of being out of a house with five children. Five young mouths to feed and backs to clothe meant not a lot of spare money for extravagances like movie tickets, but John had convinced his parents that he was going to be an actor when he grew up. Costly acting lessons were out of the question, so learning by watching the finished product would have to do. Even if they could have afforded private lessons, nobody in Palmyra was offering. Actors didn’t move to tiny towns unless they were also close to big towns with big town amenities like airports to take them to where the jobs were. That was one reason John wanted to be an actor, to get out. Palmyra had nothing to offer anyone who was interested in something other than farming.

That fateful night he was thinking hard about how grand it would be to be an actor, where he could be himself and somebody else at the same time. It was like being a twin, he thought. He was so distracted that he tripped over the legs of Mr. Byron, the local eccentric. Mr. Byron wasn’t quite homeless, and he wasn’t quite crazy, but he wasn’t quite much of anything that usual people liked to associate with. Most steered a wide berth around his 5-foot-eight frame, all angles and elbows. The hair on his head was jet black but it didn’t mean he was young. He got his hair color from a bottle of shoe polish, having realized a decade back that actual hair dye was four times as costly. Shoe polish did the trick just the same, and he didn’t mind the smell. Nobody else got close enough to notice.

Mr. Byron seemed normal when you first met him, and young ladies would take pity on him and try to befriend him. They thought that others in the town were unnecessarily rude to him, and they defended him at every opportunity. They’d make excuses for his social gaffes. This was until he turned on them, like everyone else who had gotten close. The young ladies thought he was misunderstood. In reality he was just a misanthrope.

Mr. Byron often sat on the sidewalk near the movie theater with his legs splayed out, taking up half the lane. Usually John avoided him, but this night his head was in the clouds. Later, he thought that the scrape he’d gotten on his knee from when he fell after tripping over Mr. Byron was the extent of his injuries, but he was far mistaken.

It was a month later before he noticed the change. His right side had grown heavier, thicker, denser even. His arm wouldn’t stretch out like it used to. His hand started to curling in like a lobster’s claw. At first he thought nothing of it. There wasn’t spare money for a trip to the doctor anyway, so he did as his Mama had taught him. He drank a glass of water mixed with honey and apple cider vinegar. It was the best cure they knew and usually it worked a treat. But not this time.

Mr. Byron always worked his revenge silently. His Mama taught him that “Revenge is a dish best served cold” and boy, howdy, did he love his Mama. Whatever she taught him, directly or not, he took to heart and made it his own. All of his Mama’s family had the second sight, could see right into you to know what your dreams and hopes were. Trouble was, they also knew your nightmares too. More than that, they knew how to take that raw stuff from deep in your soul and push it, shape it, like so much clay and build it up just like a mug or a vase, able to hold more than what it was before. The good ones in the family could make your dreams come true. The bad ones chose to do the same with your nightmares.

Mr. Byron was unique. He’d take your dreams, shaped them up up up, and turned them inside out, made them turn back on you so even though you got what you wished for, it wasn’t ever like how you wanted.

Normally he kept to himself and didn’t use his perverse talents. In years past some people would seek him out and try to get him to put a curse on another person in the town, someone who’d wronged them, either intentionally or not. At first Mr. Byron refused, but then he came to enjoy the opportunity to practice and hone his craft. Even people who do bad like to be good at it. He felt it was important that the results matched his plan. It was a sad day when something that was to go wrong didn’t, or worse, turned darker and deeper than anticipated. Sometimes people needed a good scare, but ended up scarred instead. It wouldn’t do to make a molehill into a mountain.

All John did that fateful night was trip over Mr. Byron’s legs, so it didn’t seem right what happened next. But that night was just the cherry on the sundae of slights and snubs Mr. Byron had suffered, to his mind.

John had never noticed Mr. Byron, and that was his undoing. John never said hello or good evening to him. He never asked how he was doing, inquired about Mr. Byron’s family, never even invited him to see a show at the theater or out for dinner. Of course, nobody ever did any of these things, but that didn’t matter to Mr. Byron, because John was the one person who crossed his path every Tuesday night for years, so John was the focal point for his rage. There’s only so much being ignored a person can take after all. Rage is like sandstone, built up tiny layer by tiny layer, week by month by year, until it is larger than a mountain and just as hard to see around.

John’s dream of being an actor was turned on him that night, but it took a while before it showed. He’d been imagining how acting was like being himself and another person at the same time when he tripped over Mr. Byron. Mr. Byron caught that wish and shaped it, turned it, and made it true in the worst way possible. John became his own twin, shaped into a chimera of impossible belief. Slowly, so slowly that he didn’t realize the cause and effect, he turned into a monster, half of him crabbed and lumpy, some strange cross of an ancient gnarled oak tree and a mutant crustacean. It was as if his dreamed-of other half was on stage all the time, and John was powerless to make the scene end.

You must be logged in to post a comment.